Thursday, 28 February 2013

Wednesday, 27 February 2013

葉問:終極一戰【製作花絮】

由英皇電影、國藝影視聯合出品之電影《葉問--終極一戰》,由冼國林監製,邱禮濤執導

故事大綱:

1949年,患有長期胃病的葉問 (黃秋生 飾) 隻身來港謀生,得一班新收徒弟照顧,在港九飯店職工總會天台開始教授詠春。其中當差的

即使生活捉襟見肘,這位一代宗師卻從未折腰,《葉問:終極一戰》還原最真實的葉問,把

Monday, 25 February 2013

Wing Chun Documentary 詠春实录

"Wing Chun" - a documentary sponsored by Shui On Land. The film shows how we can use Wing Chun and its philosophy to improve our daily life, as well as investigating its claims to be scientifically based.

Made in Hong Kong, China and Macau by an international production team, the documentary was directed by Seamus Walsh and produced by Bill Yip.

The film's narrator is Vincent Lo Hong Sui, Chairman of Shui On Land, who shares his story of how Wing Chun has informed both his business and personal life, helping him to become one of Hong Kong's most successful businessmen.

The star of the film is Master Lui Ming Fai, a student of Master Ho Kam Ming and descendant of the Great Grandmaster of Wing Chun, Ip Man. Master Lui takes us through the forms of Wing Chun as well as sharing his insight on it's elegance and practicality. The scientific testing of Wing Chun is provided by Dr. Justin Lee of Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Made in Hong Kong, China and Macau by an international production team, the documentary was directed by Seamus Walsh and produced by Bill Yip.

The film's narrator is Vincent Lo Hong Sui, Chairman of Shui On Land, who shares his story of how Wing Chun has informed both his business and personal life, helping him to become one of Hong Kong's most successful businessmen.

The star of the film is Master Lui Ming Fai, a student of Master Ho Kam Ming and descendant of the Great Grandmaster of Wing Chun, Ip Man. Master Lui takes us through the forms of Wing Chun as well as sharing his insight on it's elegance and practicality. The scientific testing of Wing Chun is provided by Dr. Justin Lee of Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Clip from Wing Chun a documentary. This is part of an interview with sifu Donald Mak at his school in Hong Kong. More information at htt://emptymindfilms.com

Wing Chun has seen explosive growth, fueled by a blockbuster movie and a legion of new followers who regard it as the most effective fighting art there is. "We have seen heat waves before and not just because of Bruce Lee" says Ip Ching, son of Grandmaster Ip Man. Experience Wing Chun in its most authentic setting as we take you on a guided tour of many of Hong Kong's top schools. Although there is only one Wing Chun it has evolved into many styles... from Ip Man Wing Chun to those that continue to develop the martial art as it spreads worldwide. "Even Ip Man modified his kungfu from his practice so we cannot stick to the word genuine anymore" says master Sam Lau, a direct student of Ip Man. Sifu Keung says simply "No matter which branch no one can say their Wing Chun is 100 percent perfect as each have their own way of practicing and if theirs is useless it will disappear."

Watch, listen and learn as teachers and students share their knowledge and experience of the principles, training and practical fighting aspects of Wing Chun. Now widely accepted as one of the most efficient and practical martial arts for both men and women in the world.

Finally a documentary that cuts through all the hype, the myths and the politics to explore Wing Chun in the authentic setting of Hong Kong and ask "is this the most effective martial art in the world?"

Wing Chun has seen explosive growth, fueled by a blockbuster movie and a legion of new followers who regard it as the most effective fighting art there is. "We have seen heat waves before and not just because of Bruce Lee" says Ip Ching, son of Grandmaster Ip Man. Experience Wing Chun in its most authentic setting as we take you on a guided tour of many of Hong Kong's top schools. Although there is only one Wing Chun it has evolved into many styles... from Ip Man Wing Chun to those that continue to develop the martial art as it spreads worldwide. "Even Ip Man modified his kungfu from his practice so we cannot stick to the word genuine anymore" says master Sam Lau, a direct student of Ip Man. Sifu Keung says simply "No matter which branch no one can say their Wing Chun is 100 percent perfect as each have their own way of practicing and if theirs is useless it will disappear."

Watch, listen and learn as teachers and students share their knowledge and experience of the principles, training and practical fighting aspects of Wing Chun. Now widely accepted as one of the most efficient and practical martial arts for both men and women in the world.

Finally a documentary that cuts through all the hype, the myths and the politics to explore Wing Chun in the authentic setting of Hong Kong and ask "is this the most effective martial art in the world?"

Experience Wing Chun in its most authentic setting as we take you on a guided tour of many of Hong Kong's top schools. Although there is only one Wing Chun it has evolved into many styles... from Ip Man Wing Chun to those that continue to develop the martial art as it spreads worldwide. "Even Ip Man modified his kungfu from his practice so we cannot stick to the word genuine anymore" says master Sam Lau, a direct student of Ip Man. Sifu Keung says simply "No matter which branch no one can say their Wing Chun is 100 percent perfect as each have their own way of practicing and if theirs is useless it will disappear."

Watch, listen and learn as teachers and students share their knowledge and experience of the principles, training and practical fighting aspects of Wing Chun. Now widely accepted as one of the most efficient and practical martial arts for both men and women in the world.

Cutting through the hype and the myths to explore Wing Chun in the schools of Hong Kong and ask "is this the most effective martial art in the world?"

Sunday, 24 February 2013

IP Man - The Final Fight 葉問之終极一戰 to open the Hong Kong 37th International Film Festival

IP Man - The Final Fight 葉問之終极一戰 to open the Hong Kong 37th International Film Festival on March 17th, 2013

Wing Chun Weapon, Butterfly Swords -Bat Cham Dao

A Social and Visual History of the Hudiedao (Butterfly Sword) in the Southern Chinese Martial Arts

Consider for instance the “bat cham dao” (the Wing Chun style name for butterfly swords) owned by Ip Man. In a recent interview Ip Ching (his son),confirmed that his father never brought a set of functional hudiedao to Hong Kong when he left Foshan in 1949. Instead, he actually brought a set of “swords” carved out of peach wood. These were the “swords” that he used when establishing Wing Chun in Hong Kong in the 1950s and laying the foundations for its global expansion.

Obviously some wooden swords are more accurate than others, but none of them are exactly like the objects they represent. It also makes a good deal of sense that Ip Man in 1949 would not really care that much about iron swords. He was not a gangster or a Triad member. He was not an opera performer. As a police officer he had carried a gun and had a good sense of what real street violence was.

Ip Man had been (and aspired to once again become) a man of leisure. He was relatively well educated, sophisticated and urbane. More than anything else he saw himself as a Confucian gentleman, and as such he was more likely to display a work of art in his home than a cold-blooded weapon.

Swords carved of peach wood have an important significance in Chinese society that goes well beyond their safety and convince when practicing martial arts forms. Peach wood swords are used in Daoist exorcisms and are thought to have demon slaying powers. In the extended version of the story of the destruction of the Shaolin Temple favored by the Triads, Heaven sends a peach wood sword to the survivors of Shaolin that they use to slay thousands of their Qing pursuers.

Hung in a home or studio, these swords are thought to convey good fortune and a certain type of energy. In fact, it was not uncommon for Confucian scholars to display a prized antique blade or a peach wood sword in their studies. Ip Man’s hudiedao appear to be a (uniquely southern) adaptation of this broader cultural tradition. As carved wooden works of art, they were only meant to have a superficial resemblance to the militia weapons of the early 19th century.

Ip Ching also relates that at a later date one of his students took these swords and had exact aluminum replicas of them created. Later these were reworked again to have a flat stainless steel blade and aluminum (latter brass) handles. Still, I think there is much to be said for the symbolism of the peach wood blade.

Butterfly swords remain one of the most iconic and easily recognizable artifacts of Southern China’s unique martial culture. Their initial creation in the late 18th or early 19th century may have been aided by recent encounters with European cutlasses and military hangers. This unique D-grip (seen in many, though not all cases) was then married to an older tradition of using double weapons housed in a single sheath.

By the 1820s, these swords were popular enough that American and British merchants in Guangdong were encountering them and adding them to their collections. By the 1830’s, we have multiple accounts of these weapons being supplied to the gentry led militia troops and braves hired by Lin in his conflicts with the British. Descriptions by Commander Bingham indicate the existence of a fully formed martial tradition in which thousands of troops were trained to fight in the open field with these swords, and even to flip them when switching between grips. (Whether flipping them is really a good idea is another matter entirely).

Increased contact between Europeans and Chinese citizens in the 1840s and 1850s resulted in more accounts of “double swords” and clear photographs and engravings showing a variety of features that are shared with modern hudiedao. The biggest difference is that most of these mid-century swords were longer and more pointed than modern swords.

Interestingly these weapons also start to appear on America’s shores as Chinese immigration from Guangdong and Fujian increased in the middle of the 19th century. Period accounts from the 1880s indicate that they were commonly employed by criminals and enforcers, and photographs from the turn of the century show that they were also used by both street performers and opera singers.

Still, these blades were in general shorter, wider and with less pronounced points, than their mid. 19th century siblings. While some individuals may have continued to carry these into the 1930s, hudiedao started to disappear from the streets as they were replaced by more modern and economical firearms. By the middle of the 20th century these items, if encountered at all, were no longer thought of as fearsome weapons of community defense or organized crime. Instead they survived as the tools of the “traditional martial arts” and opera props.

While it has touched on a variety of points, I feel that this article has made two substantive contributions to our understanding of these weapons. First, it pushed their probable date of creation back a generation or more. Rather than being the product of the late 19th century or the 1850s, we now have clear evidence of the widespread use of the hudiedao in Guangdong dating back to the 1830s, and a strong suggestion of their presence in the 1820s.

These weapons were indeed favored by civilian martial artists and various members of the “Rivers and Lakes” of southern China. Yet we have also seen that they were employed by the thousands to arm militias, braves and guards in southern China. Not only that we have accounts of thousands of individuals in the Pearl River Delta region receiving active daily instruction in their use in the late 1830s.

The popular view of hudiedao as exotic weapons of martial artists, rebels and eccentric pirates needs to be modified. These blades also symbolized the forces of “law and order.” They were produced by the thousands for government backed elite networks and paid for with public taxes. This was a reasonable choice as many members of these local militias already had some boxing experience. It would have been relatively easy to train them to hold and use these swords given what they already knew. While butterfly swords may have appeared mysterious and quintessentially “Chinese” to western observers in the 1830s, Lin supported their large scale adoption as a practical solution to a pressing problem.

This may also change how we think about the martial arts that arose in this region. For instance, the two weapons typically taught in the Wing Chun system are the “long pole” and the “bat cham do” (the style name for hudiedao). The explanations for these weapons that one normally encounters are highly exotic and focus on the wandering Shaolin monks (who were famous for their pole fighting) or secret rebel groups intent on exterminating local government officials. Often the “easily concealable” nature of the hudiedao are supposed to have made them ideal for this task (as opposed to handguns and high explosives, which are the weapons that were actually used for political assassinations during the late Qing).

Our new understanding of the historical record shows that what Wing Chun actually teaches are the two standard weapons taught to almost every militia member in the region. One typically learns pole fighting as a prelude to more sophisticated spear fighting. However, the Six and a Half Point pole form could easily work for either when training a peasant militia. And we now know that the butterfly swords were the single most common side arm issued to peasant-soldiers during the mid. 19th century in the Pearl River Delta region.

The first historically verifiable appearance of Wing Chun in Foshan was during the 1850s-1860s. This important commercial town is located literally in the heartland of the southern gentry-led militia movement. It had been the scene of intense fighting in 1854-1856 and more conflict was expected in the future.

We have no indication that Leung Jan was a secret revolutionary. He was a well known and well liked successful local businessman. Still, there are understandable reasons that the martial art which he developed would allow a highly educated and wealthy individual, to train a group of people in the use of the pole and the hudiedao. Wing Chun contains within it all of the skills one needs to raise and train a gentry led militia unit.

The evolution of Wing Chun was likely influenced by this regions unique history of militia activity and widespread (government backed) military education. I would not be at all surprised to see some of these same processes at work in other martial arts that were forming in the Pearl River Delta at the same time.

-BENJUDKINS

*Re photo: GGM Ip Man with his swords. Hong Kong, late 1960s.

Consider for instance the “bat cham dao” (the Wing Chun style name for butterfly swords) owned by Ip Man. In a recent interview Ip Ching (his son),confirmed that his father never brought a set of functional hudiedao to Hong Kong when he left Foshan in 1949. Instead, he actually brought a set of “swords” carved out of peach wood. These were the “swords” that he used when establishing Wing Chun in Hong Kong in the 1950s and laying the foundations for its global expansion.

Obviously some wooden swords are more accurate than others, but none of them are exactly like the objects they represent. It also makes a good deal of sense that Ip Man in 1949 would not really care that much about iron swords. He was not a gangster or a Triad member. He was not an opera performer. As a police officer he had carried a gun and had a good sense of what real street violence was.

Ip Man had been (and aspired to once again become) a man of leisure. He was relatively well educated, sophisticated and urbane. More than anything else he saw himself as a Confucian gentleman, and as such he was more likely to display a work of art in his home than a cold-blooded weapon.

Swords carved of peach wood have an important significance in Chinese society that goes well beyond their safety and convince when practicing martial arts forms. Peach wood swords are used in Daoist exorcisms and are thought to have demon slaying powers. In the extended version of the story of the destruction of the Shaolin Temple favored by the Triads, Heaven sends a peach wood sword to the survivors of Shaolin that they use to slay thousands of their Qing pursuers.

Hung in a home or studio, these swords are thought to convey good fortune and a certain type of energy. In fact, it was not uncommon for Confucian scholars to display a prized antique blade or a peach wood sword in their studies. Ip Man’s hudiedao appear to be a (uniquely southern) adaptation of this broader cultural tradition. As carved wooden works of art, they were only meant to have a superficial resemblance to the militia weapons of the early 19th century.

Ip Ching also relates that at a later date one of his students took these swords and had exact aluminum replicas of them created. Later these were reworked again to have a flat stainless steel blade and aluminum (latter brass) handles. Still, I think there is much to be said for the symbolism of the peach wood blade.

Butterfly swords remain one of the most iconic and easily recognizable artifacts of Southern China’s unique martial culture. Their initial creation in the late 18th or early 19th century may have been aided by recent encounters with European cutlasses and military hangers. This unique D-grip (seen in many, though not all cases) was then married to an older tradition of using double weapons housed in a single sheath.

By the 1820s, these swords were popular enough that American and British merchants in Guangdong were encountering them and adding them to their collections. By the 1830’s, we have multiple accounts of these weapons being supplied to the gentry led militia troops and braves hired by Lin in his conflicts with the British. Descriptions by Commander Bingham indicate the existence of a fully formed martial tradition in which thousands of troops were trained to fight in the open field with these swords, and even to flip them when switching between grips. (Whether flipping them is really a good idea is another matter entirely).

Increased contact between Europeans and Chinese citizens in the 1840s and 1850s resulted in more accounts of “double swords” and clear photographs and engravings showing a variety of features that are shared with modern hudiedao. The biggest difference is that most of these mid-century swords were longer and more pointed than modern swords.

Interestingly these weapons also start to appear on America’s shores as Chinese immigration from Guangdong and Fujian increased in the middle of the 19th century. Period accounts from the 1880s indicate that they were commonly employed by criminals and enforcers, and photographs from the turn of the century show that they were also used by both street performers and opera singers.

Still, these blades were in general shorter, wider and with less pronounced points, than their mid. 19th century siblings. While some individuals may have continued to carry these into the 1930s, hudiedao started to disappear from the streets as they were replaced by more modern and economical firearms. By the middle of the 20th century these items, if encountered at all, were no longer thought of as fearsome weapons of community defense or organized crime. Instead they survived as the tools of the “traditional martial arts” and opera props.

While it has touched on a variety of points, I feel that this article has made two substantive contributions to our understanding of these weapons. First, it pushed their probable date of creation back a generation or more. Rather than being the product of the late 19th century or the 1850s, we now have clear evidence of the widespread use of the hudiedao in Guangdong dating back to the 1830s, and a strong suggestion of their presence in the 1820s.

These weapons were indeed favored by civilian martial artists and various members of the “Rivers and Lakes” of southern China. Yet we have also seen that they were employed by the thousands to arm militias, braves and guards in southern China. Not only that we have accounts of thousands of individuals in the Pearl River Delta region receiving active daily instruction in their use in the late 1830s.

The popular view of hudiedao as exotic weapons of martial artists, rebels and eccentric pirates needs to be modified. These blades also symbolized the forces of “law and order.” They were produced by the thousands for government backed elite networks and paid for with public taxes. This was a reasonable choice as many members of these local militias already had some boxing experience. It would have been relatively easy to train them to hold and use these swords given what they already knew. While butterfly swords may have appeared mysterious and quintessentially “Chinese” to western observers in the 1830s, Lin supported their large scale adoption as a practical solution to a pressing problem.

This may also change how we think about the martial arts that arose in this region. For instance, the two weapons typically taught in the Wing Chun system are the “long pole” and the “bat cham do” (the style name for hudiedao). The explanations for these weapons that one normally encounters are highly exotic and focus on the wandering Shaolin monks (who were famous for their pole fighting) or secret rebel groups intent on exterminating local government officials. Often the “easily concealable” nature of the hudiedao are supposed to have made them ideal for this task (as opposed to handguns and high explosives, which are the weapons that were actually used for political assassinations during the late Qing).

Our new understanding of the historical record shows that what Wing Chun actually teaches are the two standard weapons taught to almost every militia member in the region. One typically learns pole fighting as a prelude to more sophisticated spear fighting. However, the Six and a Half Point pole form could easily work for either when training a peasant militia. And we now know that the butterfly swords were the single most common side arm issued to peasant-soldiers during the mid. 19th century in the Pearl River Delta region.

The first historically verifiable appearance of Wing Chun in Foshan was during the 1850s-1860s. This important commercial town is located literally in the heartland of the southern gentry-led militia movement. It had been the scene of intense fighting in 1854-1856 and more conflict was expected in the future.

We have no indication that Leung Jan was a secret revolutionary. He was a well known and well liked successful local businessman. Still, there are understandable reasons that the martial art which he developed would allow a highly educated and wealthy individual, to train a group of people in the use of the pole and the hudiedao. Wing Chun contains within it all of the skills one needs to raise and train a gentry led militia unit.

The evolution of Wing Chun was likely influenced by this regions unique history of militia activity and widespread (government backed) military education. I would not be at all surprised to see some of these same processes at work in other martial arts that were forming in the Pearl River Delta at the same time.

-BENJUDKINS

*Re photo: GGM Ip Man with his swords. Hong Kong, late 1960s.

Friday, 22 February 2013

Wing Chun Ip Man - The Final Fight Trailer《葉問 - 終極一戰》

由英皇電影、國藝影視聯合出品之電影《葉問--終極一戰》,由冼國林監製,邱禮濤執導

故事大綱:

1949年,患有長期胃病的葉問 (黃秋生 飾) 隻身來港謀生,得一班新收徒弟照顧,在港九飯店職工總會天台開始教授詠春。其中當差的

即使生活捉襟見肘,這位一代宗師卻從未折腰,《葉問:終極一戰》還原最真實的葉問,把

Thursday, 21 February 2013

Wednesday, 20 February 2013

Wing Chun / Ving Tsun Chi Sau by Sifu David Peterson

"In effect, Chi Sau gives us the ability to "see" things about the opponent's attack that our eyes cannot see, to 'read his/her intentions' at a neural level, thus accelerating our potential to respond effectively. Practising 'Chi Sau' with 'soft force', or with pre-arranged sequences, unrealistic counterattacks from impossible situations, and the implementation of 'rules of engagement' (such as no attacking to the head, etc.). totally contradict the purpose of the exercise. This is not to say that we have to try to bash our training partner at every opportunity, but that we need to make the drill as close to reality as possible. In combat, if we clash with an opponent, force will be applied, especially the enemy (after all, he/she is trying o hit you!) Therefore, in Chi Sau practice, we need to apply forward force, with an intention to attack if and when an opening occurs or an attack succeeds. The energy used should be flexible, like compressed rubber, not stiff-like solid steel, with firmness and not tension. This approach should begin with the 'single-hand' exercise (Dan Chi Sau) and continue on through to the Gwoh Sau or 'free-attack' stage. Only in this way, free of restrictions and with an emphasis on attacking the man rather than 'chasing the arms', will the Chi Sau drill bear any relevance to real combat."

-David Peterson

"Look Beyond The Pointing Finger

-The Combat Philosophy of Wong Shun Leung"

*Get a copy of this book if you wish to learn and mind-prepare yourself how to survive street combat...for practitioners of all Martial Arts system.

-David Peterson

"Look Beyond The Pointing Finger

-The Combat Philosophy of Wong Shun Leung"

*Get a copy of this book if you wish to learn and mind-prepare yourself how to survive street combat...for practitioners of all Martial Arts system.

The Wing Chun Compendium by Wayne Belonoha

Wing Chun has a number of striking tools at its disposal, from the most popular and common straight punch, to the less used crane fist. While many of these techniques can be used to strike a specific point, the most common weapon is the phoenix eye fist.

The phoenix fist is created by extending the index finger and bending it at the second knuckle. The rest of the fingers are placed like in a regular fist. Place your thumb into the bend of the second knuckle and squeeze to make the fist tight as a rock. Striking is done with the extended knuckle.

The phoenix fist is created by extending the index finger and bending it at the second knuckle. The rest of the fingers are placed like in a regular fist. Place your thumb into the bend of the second knuckle and squeeze to make the fist tight as a rock. Striking is done with the extended knuckle.

A Social and Visual History of the Hudiedao (Butterfly Sword) in the Southern Chinese Martial Arts

The next photograph from the same period presents us with the opposite challenge. It gives us a wonderfully detailed view of the weapons, but any appropriate context for understanding their use or meaning is missing. Given it’s physical size and technology of production, this undated photograph was probably taken in the 1860s. It was likely taken in either San Francisco or Hong Kong, though it is impossible to rule out some other location.

On the verso we find an ink stamp for “G. Harrison Gray” (evidently the photographer). Images like this might be produced either for sale to the subject (hence all of the civil war portraits that one sees in American antique circles), or they might have been reproduced for sale to the general public. Given the colorful subject matter of this image I would guess that the latter is most likely the case, but again, it is impossible to be totally certain.

The young man in the photo (labeled “Chinese Soldier”) is shown in the ubiquitous wicker helmet and is armed only with a set of exceptionally long hudedao. These swords feature a slashing and chopping blade that terminates in a hatchet point, commonly seen on existing examples. The guards on these knives appear to be relatively thin and the quillion is not as long or wide as some examples. I would hazard a guess that both are made of steel rather than brass. Given the long blade and light handle, these weapons likely felt top heavy, though there are steps that a skilled swordsmith could take to lessen the effect.

It is interesting to note that the subject of the photograph is holding the horizontal blade backwards. It was a common practice for photographers of the time to acquire costumes, furniture and even weapons to be used as props in a photograph. It is likely that these swords actually belonged to G. Harrison Gray or his studio and the subject has merely been dressed to look like a “soldier.” In reality he may never have handled a set of hudiedao before.

-BENJUDKINS

*Re photo; 1860s photograph of a “Chinese Soldier” with butterfly swords. Subject unknown, taken by G. Harrison Gray.

On the verso we find an ink stamp for “G. Harrison Gray” (evidently the photographer). Images like this might be produced either for sale to the subject (hence all of the civil war portraits that one sees in American antique circles), or they might have been reproduced for sale to the general public. Given the colorful subject matter of this image I would guess that the latter is most likely the case, but again, it is impossible to be totally certain.

The young man in the photo (labeled “Chinese Soldier”) is shown in the ubiquitous wicker helmet and is armed only with a set of exceptionally long hudedao. These swords feature a slashing and chopping blade that terminates in a hatchet point, commonly seen on existing examples. The guards on these knives appear to be relatively thin and the quillion is not as long or wide as some examples. I would hazard a guess that both are made of steel rather than brass. Given the long blade and light handle, these weapons likely felt top heavy, though there are steps that a skilled swordsmith could take to lessen the effect.

It is interesting to note that the subject of the photograph is holding the horizontal blade backwards. It was a common practice for photographers of the time to acquire costumes, furniture and even weapons to be used as props in a photograph. It is likely that these swords actually belonged to G. Harrison Gray or his studio and the subject has merely been dressed to look like a “soldier.” In reality he may never have handled a set of hudiedao before.

-BENJUDKINS

*Re photo; 1860s photograph of a “Chinese Soldier” with butterfly swords. Subject unknown, taken by G. Harrison Gray.

Ving Tsun / Wing Chun Class, Malaysia 詠春拳術班, 馬來西亞

Pusat Komuniti Bandar Manjalara,

Jalan Medan Putra 1,

Bandar Manjalara,

52200 Kuala Lumpur.

Tuesday, 8.00pm-10.00pm

Dewan Orang Ramai Kampung Salak Selatan,

Lot 7895, Jalan Satu, Salak Selatan Baru.

57100 Kuala Lumpur.

Wednesday, 8.00pm-10.00pm

MCA Cawangan,

Jalan Perisa 4,

Taman Gembira,

58200 Kuala Lumpur.

Saturday, 9.00am-11.00am

USJ 16/2A Subang Jaya.

47630 Selangor.

Saturday, 3.00pm-5.00pm

Tokong Dong Teng Keng

16G, Jalan Temiang, 70200,

Seremban. Negeri Sembilan.

Sunday, 8.00am-10.00am

A Social and Visual History of the Hudiedao (Butterfly Sword) in the Southern Chinese Martial Arts

Lastly there are shorter, thicker blades, designed with cutting and hacking in mind. These more closely resemble the type favored by Wushu performers and modern martial artists. Some of these weapons could be carried in a concealed manner, yet they are also better balanced and have a stronger stabbing point than most of the inexpensive replicas being made today. It is also interesting to note that these shorter, more modern looking knives, can be quite uncommon compared to the other blade types listed above.

I am hesitant to assign names or labels to these different sorts of blades. That may seem counter-intuitive, but the very existence of “labels” implies a degree of order and standardization that may not have actually existed when these swords were made. 19th century western observers simply referred to everything that they saw as a “double sword” and chances are good that their Chinese agents did the same. Given that most of these weapons were probably made in small shops and to the exact specifications of the individuals who commissioned them the idea of different “types” of hudiedao seems a little misleading.

What defined a “double sword” to both 19th century Chinese and western observers in Guangdong, was actually how they were fitted and carried in the scabbard. These scabbards were almost always leather, and they did not separate the blades into two different channels or compartments (something that is occasionally seen in northern double weapons). Beyond that, a wide variety of blade configurations, hand guards and levels of ornamentation could be used. I am still unclear when the term “hudiedao” came into common use, or how so many independent observers and careful collectors could have missed it.

-BENJUDKINS

*Re photo;

These hudiedao are more reminiscent of the blades favored by modern Wing Chun students. They show considerable wear and date to either the middle or end of the 19th century. The tips of the blades are missing and may have been broken or rounded off through repeated sharpening. I suspect that when these swords were new they had a more hatchet shaped tip. Their total length is 49 cm. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com/

I am hesitant to assign names or labels to these different sorts of blades. That may seem counter-intuitive, but the very existence of “labels” implies a degree of order and standardization that may not have actually existed when these swords were made. 19th century western observers simply referred to everything that they saw as a “double sword” and chances are good that their Chinese agents did the same. Given that most of these weapons were probably made in small shops and to the exact specifications of the individuals who commissioned them the idea of different “types” of hudiedao seems a little misleading.

What defined a “double sword” to both 19th century Chinese and western observers in Guangdong, was actually how they were fitted and carried in the scabbard. These scabbards were almost always leather, and they did not separate the blades into two different channels or compartments (something that is occasionally seen in northern double weapons). Beyond that, a wide variety of blade configurations, hand guards and levels of ornamentation could be used. I am still unclear when the term “hudiedao” came into common use, or how so many independent observers and careful collectors could have missed it.

-BENJUDKINS

*Re photo;

These hudiedao are more reminiscent of the blades favored by modern Wing Chun students. They show considerable wear and date to either the middle or end of the 19th century. The tips of the blades are missing and may have been broken or rounded off through repeated sharpening. I suspect that when these swords were new they had a more hatchet shaped tip. Their total length is 49 cm. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com/

Monday, 18 February 2013

Saturday, 16 February 2013

How to Develop Chi Power by William Cheung (Wing Chun Master) 1st Edition 1986

The circulation meridians also belong to the element of fire, and are yin property. Each meridian has nine pressure points. The proper exercise of these pressure points can cure heart trouble and loss of memory.

This book covers Chi Exercises, to promote the flow of chi using the first form of the Wing Chun system 'Siu Nim Tau.'

It is designed to train for improvement of breathing, coordination, concentration, balance, independent movement of the limbs, and mind and body coordination. Most important of all, doing this form improves the

internal energy flow.

This form shown with illustrations is divided into four sections:

1. Commencement; 2. Tan Sao and Fook Sao; 3. Gum Sao and Bil Sao and 4. Tan Sao, Garn Sao, and Bong Sao

This book covers Chi Exercises, to promote the flow of chi using the first form of the Wing Chun system 'Siu Nim Tau.'

It is designed to train for improvement of breathing, coordination, concentration, balance, independent movement of the limbs, and mind and body coordination. Most important of all, doing this form improves the

internal energy flow.

This form shown with illustrations is divided into four sections:

1. Commencement; 2. Tan Sao and Fook Sao; 3. Gum Sao and Bil Sao and 4. Tan Sao, Garn Sao, and Bong Sao

How to Develop Chi Power by William Cheung (Wing Chun Master)

The root of the way of life, or birth and change is chi (Qi); the myriad things of heaven and earth all obey this law. Thus chi in the periphery envelopes heaven and earth; Chi in the interior activates them.

The source wherefrom the sun, moon and stars derive their light; The thunder, rain, wind and cloud, their being, the four seasons and the myriad things their birth, growth, gathering and storing; all this is brought about by chi. Man's possession of life is completely dependent upon this chi.

-Nei Ching

Classic of Internal Medicine

2697-2596 B.C.

Philosophy of Wing Chun

One who excels as a warrior does not appear formidable;

One who excels in fighting is never aroused in anger.

One who excels in defeating his enemy does not join issues;

One who excels in employing others humbles himself before them. This is the virtue of non-contention and matching the sublimity of heaven.

The aim of Wing Chun Kung Fu is to develop physical, mental and spiritual awareness. These elements transcend to a higher level of life. Self-awareness, self-respect and a duty to serve should be the goal of every martial artist. The practitioner should meditate on these principles and make peace through the study of Kung Fu- a way of life.

There are six chapters, namely:

Chapter 1: The Nature of Chi: Yin/Yang and the Five Elements

Chapter 2: The Flow of Chi: Pressure Points and Meridians

Chapter 3: Promoting the Flow of Chi: Chi Exercises

Chapter 4: Techniques: Basic Arm Movements

Chapter 5: Cultivating Chi: Siu Nim Tao

Wing Chun techniques combined into an exercise for training reflexes, coordination, and improving power through the cultivation of Chi.

Chapter 6: Engaging an Opponent's Chi: Basic Chi Sao Exercises

About the Author:

William Cheung 張卓慶 is a Chinese Wing Chun Gung Fu practitioner and currently the Grandmaster of his lineage, Wing Chun 'Traditional Wing Chun' (TWC).

William Cheung attained Bachelor of Economics from the Australian National University, after graduating from secondary school in Hong Kong. William Cheung is also a certified Doctor of Chinese Medicine under the Chinese Medicine Registration Board of Victoria, and a member of the Australian Chinese Traditional Orthopaedics Association Inc. He has also been invited as a Guest Professor to Foshan Sports University (China), and as a Senior Research Professor of the Bone Research Department to Beijing Chinese Medical University (China).

At a young age William Cheung started his training in Wing Chun Gung Fu under the Great Grandmaster Ip Man.

The source wherefrom the sun, moon and stars derive their light; The thunder, rain, wind and cloud, their being, the four seasons and the myriad things their birth, growth, gathering and storing; all this is brought about by chi. Man's possession of life is completely dependent upon this chi.

-Nei Ching

Classic of Internal Medicine

2697-2596 B.C.

Philosophy of Wing Chun

One who excels as a warrior does not appear formidable;

One who excels in fighting is never aroused in anger.

One who excels in defeating his enemy does not join issues;

One who excels in employing others humbles himself before them. This is the virtue of non-contention and matching the sublimity of heaven.

The aim of Wing Chun Kung Fu is to develop physical, mental and spiritual awareness. These elements transcend to a higher level of life. Self-awareness, self-respect and a duty to serve should be the goal of every martial artist. The practitioner should meditate on these principles and make peace through the study of Kung Fu- a way of life.

There are six chapters, namely:

Chapter 1: The Nature of Chi: Yin/Yang and the Five Elements

Chapter 2: The Flow of Chi: Pressure Points and Meridians

Chapter 3: Promoting the Flow of Chi: Chi Exercises

Chapter 4: Techniques: Basic Arm Movements

Chapter 5: Cultivating Chi: Siu Nim Tao

Wing Chun techniques combined into an exercise for training reflexes, coordination, and improving power through the cultivation of Chi.

Chapter 6: Engaging an Opponent's Chi: Basic Chi Sao Exercises

About the Author:

William Cheung 張卓慶 is a Chinese Wing Chun Gung Fu practitioner and currently the Grandmaster of his lineage, Wing Chun 'Traditional Wing Chun' (TWC).

William Cheung attained Bachelor of Economics from the Australian National University, after graduating from secondary school in Hong Kong. William Cheung is also a certified Doctor of Chinese Medicine under the Chinese Medicine Registration Board of Victoria, and a member of the Australian Chinese Traditional Orthopaedics Association Inc. He has also been invited as a Guest Professor to Foshan Sports University (China), and as a Senior Research Professor of the Bone Research Department to Beijing Chinese Medical University (China).

At a young age William Cheung started his training in Wing Chun Gung Fu under the Great Grandmaster Ip Man.

Friday, 15 February 2013

Ving Tsun / Wing Chun Master Wong Shun Leung's ANSWER

Ground Fighting

Wong Shun Leung's Answer on the Question of "From the fights that you had, did you find that you needed to fight on the ground?"

"The situation where you need to wrestle is when both opponents want to grab. Western boxing is supposed to be hitting, but you still see situations where they want to hold on to each other. This is because one of them is scared. If you are scared then you will try to hold onto your opponent. It is very difficult for someone to lock or hold onto you if you know Wing Chun. You can stop the other guy holding or grabbing. If someone grabs you, you will only try to grab back if you are scared. But if you are not scared, then he cannot force you into a wrestling situation."

Wong Shun Leung's Answer on the Question of "From the fights that you had, did you find that you needed to fight on the ground?"

"The situation where you need to wrestle is when both opponents want to grab. Western boxing is supposed to be hitting, but you still see situations where they want to hold on to each other. This is because one of them is scared. If you are scared then you will try to hold onto your opponent. It is very difficult for someone to lock or hold onto you if you know Wing Chun. You can stop the other guy holding or grabbing. If someone grabs you, you will only try to grab back if you are scared. But if you are not scared, then he cannot force you into a wrestling situation."

Hong Kong Movie Stars - Wing Chun Contribution

Sammo Hung 洪金寶 & Yun Biu 元彪,

They have working together since the first Hong Kong Kung Fu, Wing Chun movie, "Bai Kar Zai" 敗家仔, the story line is about the Master Leung Yii Tai 梁二娣 and Leung Bik 梁壁, and the latest Wing Chun Movie is "The Legend is Born" 葉問前傳"

They have working together since the first Hong Kong Kung Fu, Wing Chun movie, "Bai Kar Zai" 敗家仔, the story line is about the Master Leung Yii Tai 梁二娣 and Leung Bik 梁壁, and the latest Wing Chun Movie is "The Legend is Born" 葉問前傳"

Wing Chun / Ving Tsun Master Ip Chun's statement to Brandon Chan 陳賢武

(Chinese Subtitle)

(English Subtitle)

Wing Chun Master Ip Chun's statement to “Prof. Dr." Brandon Chan 陈贤武/陈法澄, Malaysia (English Subtitle)

Report from YB. Fong Kui Lun 方贵伦 http://fongkuilun.blogspot.com/2010/05/blog-post_24.html

News from Guang Ming Papers: http://www.guangming.com.my/node/74904

Ving Tsun / Wing Chun Wooden Dummy

Custom made a Ving Tsun / Wing Chun Wooden Dummy for yourself, you will feel more excited and passionate in the particular training!

Thursday, 14 February 2013

Wednesday, 13 February 2013

Wing Chun In A Modern MMA World - Phillip Romero

"I’m by no means opposed to MMA. There are some great fighters in the MMA world that traditional players should think twice before dismissing as “not legit”, or as poor fighters. Practising a traditional style that has forms or katas while you wear a traditional uniform and use Chinese, Japanese or Korean during your training does not necessarily make you more dangerous than someone who trains to fight wearing Speedos in an octagon. My only disappointment is that in the mind of the public it seems to be a zero-sum game. The more stock they place in MMA, the less respect they seem to have for traditional arts like Wing Chun."

-- Spread of our interview with Sifu Phillip Romero from the upcoming Issue #10. Like this?

-- Spread of our interview with Sifu Phillip Romero from the upcoming Issue #10. Like this?

Tuesday, 12 February 2013

A Dictionary of Wing Chun Grandmaster Ip Chun

Everyone has a dictionary and philosophy of himself in various career, industry and thought. What is the dictionary of Wing Chun Grandmaster, Ip Chun?

Ip Chun Si-Fu, the eldest son of the late Grandmaster Yip Man (Yip Gei-Man), was born in 1924 in Foshan in the Zheyieng Delta region of the Guangdong province of Southern China. He began studying Wing Chun with his father when he was 7 years old, however he admits that he did not really want to learn at that time and that he remembers relatively little from that early tuition.

When the communist revolution swept through China in 1949, the communists began to persecute the wealthy, the influential and anyone connected to the Kuomintang (the political party founded by Sun Yat-Sen, the first president of the Republic of China). Since Ip Man was both wealthy and a Captain of Local Police patrols of Namhoi, he felt forced to leave China, finally settling in Hong Kong after a short stay in Macao with friends. However, being only 24, Ip Chun stayed behind to continue his studies at University studying Chinese history and traditional Chinese music. He also researched Chinese Philosophy, Buddhism and Chinese Poetry.

In 1950 Yip Man began teaching Wing Chun in Hong Kong to members of the Restaurant Workers Union to earn a living. Over the following 22 years he taught hundreds of students, some of whom trained to an exceptionally high standard, such as Wong Shun Leung, Lok Yiu, Leung Sheung and Tsui Shun Tin. Ip Chun meanwhile, finished his studies and chose teaching as a profession. He taught Chinese history, music and science, whilst during his leisure time he helped the Chinese Foshan Entertainment Department organize Chinese Operas. During this period he was awarded 'The person with the most potential in Chinese art' for music research. Unfortunately Mao Tze Tung's policies and campaigns meant that in 1962 Ip Chun and his younger brother Ip Ching , were forced to leave China for Hong Kong, where they lived with their father.

During the day Ip Chun worked as an accountant and newspaper reporter, at the same time in the evenings he restarted his Wing Chun studies with his father, maintaining the Chinese tradition of passing down the Kung Fu skills from father to son. Master Ip Chun trained with his father most evenings and since Grandmaster Ip Man's home in Tung Choi Street, Mong Kok was also his Wing Chun school, Master Ip Chun was able to witness and study his father's Wing Chun and his teaching methods every evening.

In accordance with his father's wishes, in 1965, Ip Chun began participating in the work of the Ving Tsun Athletic Association (VTAA) founding group and became a founding member of the VTAA proper. The association formally came into being in 1968 and Ip Chun was issued with the membership number nine. During the first three years of the association's existence he took on the responsibility of Treasurer and later was appointed as Chairman. The VTAA has compiled three magazines, of which one is yet to be published. Ip Chun was the compiler for two of those and was further elected to the position of committee coordinator/ chief coordinator. From conception through to the present day, Ip Chun has worked with the association and has shared in its trials and tribulations as it has grown and become the success it is today.

1967 Master Ip Chun began teaching Wing Chun in Hong Kong with his father's blessing and it is testimony indeed that some of those first students such as Ho Po Kai and Leung Chung Wai still train with him today. Later between 1970 and 1971 Master Ip Chun and Sifu Lau Hon Lam taught a class of around 20 students in Ho Man Tin. Students in that class included Leung Ting Kwok (Patrick) who now teaches for Master Ip.

On 1st December 1972 Grandmaster Ip Man passed away aged 79. Six weeks before, knowing he had not long to live he made the supreme effort to commit the Siu Nim Tao, Chum Kiu and Muk Yan Jong forms to 8 mm film in order to record and preserve the pure Wing Chun system, this crucial piece of film footage he entrusted to his two sons for posterity, and true to his father's wishes Master Ip Chun has carried on his teachings, keeping Wing Chun pure and maintaining its principles and concepts.

Today at over eighty six years of age, Master Ip Chun is one of the most successful Wing Chun teachers in Hong Kong teaching five days a week to individuals at his home or to small groups at the Ving Tsun Athletic Association, as well as teaching a class in Shatin once a week. Several of his senior Hong Kong students now teach at locations around Hong Kong including several of the Universities. Master Ip Chun also has seven students living and teaching in England, America, South Africa and Australia, who represent him and help him spread his father's teaching around the World.

Between 1985 and 2001, Ip Chun travelled the length and breadth of the world to promote and conduct Wing Chun seminars and in the process receiving various accolades, before semi retiring in 2001 to concentrate on teaching his classes in Hong Kong.

In 1992 Master Ip Chun decided to set up the Ip Chun Wing Chun Kuen Martial Arts Association to certify and authenticate those of his senior students who have attained instructor level under his personal tuition in Hong Kong and whom, with his express permission, teach for and represent Master Ip Chun around the world. He has a number of students who directly under his Wing Chun/Ving Tsun System. Certified and authorized Sifu/Instructors are stated in Hong Kong, Singapore, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, South Africa and U.S.A.

Ip Chun Si-Fu, the eldest son of the late Grandmaster Yip Man (Yip Gei-Man), was born in 1924 in Foshan in the Zheyieng Delta region of the Guangdong province of Southern China. He began studying Wing Chun with his father when he was 7 years old, however he admits that he did not really want to learn at that time and that he remembers relatively little from that early tuition.

When the communist revolution swept through China in 1949, the communists began to persecute the wealthy, the influential and anyone connected to the Kuomintang (the political party founded by Sun Yat-Sen, the first president of the Republic of China). Since Ip Man was both wealthy and a Captain of Local Police patrols of Namhoi, he felt forced to leave China, finally settling in Hong Kong after a short stay in Macao with friends. However, being only 24, Ip Chun stayed behind to continue his studies at University studying Chinese history and traditional Chinese music. He also researched Chinese Philosophy, Buddhism and Chinese Poetry.

In 1950 Yip Man began teaching Wing Chun in Hong Kong to members of the Restaurant Workers Union to earn a living. Over the following 22 years he taught hundreds of students, some of whom trained to an exceptionally high standard, such as Wong Shun Leung, Lok Yiu, Leung Sheung and Tsui Shun Tin. Ip Chun meanwhile, finished his studies and chose teaching as a profession. He taught Chinese history, music and science, whilst during his leisure time he helped the Chinese Foshan Entertainment Department organize Chinese Operas. During this period he was awarded 'The person with the most potential in Chinese art' for music research. Unfortunately Mao Tze Tung's policies and campaigns meant that in 1962 Ip Chun and his younger brother Ip Ching , were forced to leave China for Hong Kong, where they lived with their father.

During the day Ip Chun worked as an accountant and newspaper reporter, at the same time in the evenings he restarted his Wing Chun studies with his father, maintaining the Chinese tradition of passing down the Kung Fu skills from father to son. Master Ip Chun trained with his father most evenings and since Grandmaster Ip Man's home in Tung Choi Street, Mong Kok was also his Wing Chun school, Master Ip Chun was able to witness and study his father's Wing Chun and his teaching methods every evening.

In accordance with his father's wishes, in 1965, Ip Chun began participating in the work of the Ving Tsun Athletic Association (VTAA) founding group and became a founding member of the VTAA proper. The association formally came into being in 1968 and Ip Chun was issued with the membership number nine. During the first three years of the association's existence he took on the responsibility of Treasurer and later was appointed as Chairman. The VTAA has compiled three magazines, of which one is yet to be published. Ip Chun was the compiler for two of those and was further elected to the position of committee coordinator/ chief coordinator. From conception through to the present day, Ip Chun has worked with the association and has shared in its trials and tribulations as it has grown and become the success it is today.

1967 Master Ip Chun began teaching Wing Chun in Hong Kong with his father's blessing and it is testimony indeed that some of those first students such as Ho Po Kai and Leung Chung Wai still train with him today. Later between 1970 and 1971 Master Ip Chun and Sifu Lau Hon Lam taught a class of around 20 students in Ho Man Tin. Students in that class included Leung Ting Kwok (Patrick) who now teaches for Master Ip.

On 1st December 1972 Grandmaster Ip Man passed away aged 79. Six weeks before, knowing he had not long to live he made the supreme effort to commit the Siu Nim Tao, Chum Kiu and Muk Yan Jong forms to 8 mm film in order to record and preserve the pure Wing Chun system, this crucial piece of film footage he entrusted to his two sons for posterity, and true to his father's wishes Master Ip Chun has carried on his teachings, keeping Wing Chun pure and maintaining its principles and concepts.

Today at over eighty six years of age, Master Ip Chun is one of the most successful Wing Chun teachers in Hong Kong teaching five days a week to individuals at his home or to small groups at the Ving Tsun Athletic Association, as well as teaching a class in Shatin once a week. Several of his senior Hong Kong students now teach at locations around Hong Kong including several of the Universities. Master Ip Chun also has seven students living and teaching in England, America, South Africa and Australia, who represent him and help him spread his father's teaching around the World.

Between 1985 and 2001, Ip Chun travelled the length and breadth of the world to promote and conduct Wing Chun seminars and in the process receiving various accolades, before semi retiring in 2001 to concentrate on teaching his classes in Hong Kong.

In 1992 Master Ip Chun decided to set up the Ip Chun Wing Chun Kuen Martial Arts Association to certify and authenticate those of his senior students who have attained instructor level under his personal tuition in Hong Kong and whom, with his express permission, teach for and represent Master Ip Chun around the world. He has a number of students who directly under his Wing Chun/Ving Tsun System. Certified and authorized Sifu/Instructors are stated in Hong Kong, Singapore, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, South Africa and U.S.A.

The Stars with Wing Chun GM Ip Chun

Donnie Yen stars for The Movie IP MAN and IP MAN 2 and Tony Leung stars for THE GRANDMASTERS. Both actors are in different category, Donnie Yen is an action star and Tony Leung is non-action star. They are facing many challenges and hard working on Wing Chun Training by GM Ip Chun and assistants to get them know he history as background of Wing Chun an his father, Ip man. They try to do the best to represent The Great Grandmaster, Ip Man in the movie.

Monday, 11 February 2013

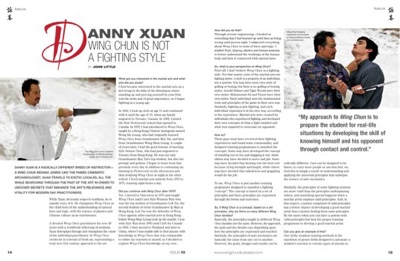

WING CHUN IS NOT A FIGHTING STYLE - Danny Xuan

"Basically, the principles taught in different Wing Chun families are the same. However, the approach, the path and the details vary depending upon how the principles are expressed and reached. Similarly, the principles of auto mechanics are basically the same from one car to another. However, the goals, designs and results can be radically different. Cars can be designed to be faster, to carry more people or use less fuel, etc. And this is simply a result of understanding and applying the universal principles that underpin the science of auto mechanics. Similarly, the principles of some fighting systems are more valid than the principles underpinning others, and something special happens when a martial artist employs valid principles. And, in this respect, a system comprised of valid principles has a better chance of developing a good martial artist than a system lacking these same principles. By the same token you can have a system with valid principles but lack the proper training programme to develop a good martial artist."

For order details, please refer to our website:

http://www.wingchunillustrated.com/buy

For order details, please refer to our website:

http://www.wingchunillustrated.com/buy

Friday, 8 February 2013

THE GRANDMASTERS - Ip Man, starring by Tony Leung

"A story that stands out is during one of our outdoor fight scenes. At night, under the rain, which took over a month to shoot, where I had to perform many of the stunts for Tony was quite a horrible experience. We were working from sunset to sunrise every night, with water up to our ankles due to the streets being intentionally flooded. We were soaking wet all night in very cold weather forcing us to wear wetsuits under our costumes, which ended with Tony suffering tracheitis [a bacterial infection of the windpipe] and I with a partially torn hamstring. However, I must say, in the end it was worth it."

-- Spread of our cover interview with Sifu Henry Araneda from the upcoming Issue #10. Like this? Then please spread the word by clicking the “Like” or "Share" link. Thanks!

You can read Wing Chun Illustrated whichever way you prefer—Print, PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone, iPod Touch, and Kindle Fire. You can even read WCI on the new Internet-connected Smart TVs. WCI ships worldwide! For order details, please refer to our website:

http://www.wingchunillustrated.com/buy

-- Spread of our cover interview with Sifu Henry Araneda from the upcoming Issue #10. Like this? Then please spread the word by clicking the “Like” or "Share" link. Thanks!

You can read Wing Chun Illustrated whichever way you prefer—Print, PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone, iPod Touch, and Kindle Fire. You can even read WCI on the new Internet-connected Smart TVs. WCI ships worldwide! For order details, please refer to our website:

http://www.wingchunillustrated.com/buy

Wing Chun 108 Muk Yan Jong (Wooden Dummy) Form

108 Muk Yan Jong

by Moy Yat

Published in 1974

It is the first book in English to show the entire wooden dummy form, and written by an authentic first generation student of Yip Man. This probably has the coolest book cover as well, with the front cover's top flaps opening up to reveal a "key" to the Wooden Dummy form, while the first cover page has you looking through a keyhole to see Yip Man and Moy Yat.

This book starts with a preface by Moy Yat, followed by a one page brief history of Wing Chun (Ving Tsun), Yim Ving Tsun, Yip Man and Moy Yat.

The Author at 24 became the youngest Wing Chun sifu.

The rest of the book is the actual dummy form, in black and white photos, performed by Lee Sai Jow.

There is almost no text in the book. What there is of it, is in a one-line format across the bottom of the page. It covers what the dummy is used for, why it's called Muk Yan Jong.

There are 3 main categories

1. neutralization

2. confrontations and

3. counters and attacks.

Moy Yat says you move around the dummy because the dummy doesn't move or respond like a real "live" person, so you have to. He then discusses why other people's forms and dummy is different-irregular teachings by Yip Man, yet according to him, the correct sequence isn't important. Only that you have mastered and understood what you've learned.

The end of the book gives a layout and measurements on how to build a Wooden Dummy from 3 views as well as measurements for the arms and leg. The last 3 pages show 3 ink carvings of the history of Wing Chun done by Moy Yat.

-Dr. John Crescione

by Moy Yat

Published in 1974

It is the first book in English to show the entire wooden dummy form, and written by an authentic first generation student of Yip Man. This probably has the coolest book cover as well, with the front cover's top flaps opening up to reveal a "key" to the Wooden Dummy form, while the first cover page has you looking through a keyhole to see Yip Man and Moy Yat.

This book starts with a preface by Moy Yat, followed by a one page brief history of Wing Chun (Ving Tsun), Yim Ving Tsun, Yip Man and Moy Yat.

The Author at 24 became the youngest Wing Chun sifu.

The rest of the book is the actual dummy form, in black and white photos, performed by Lee Sai Jow.

There is almost no text in the book. What there is of it, is in a one-line format across the bottom of the page. It covers what the dummy is used for, why it's called Muk Yan Jong.

There are 3 main categories

1. neutralization

2. confrontations and

3. counters and attacks.

Moy Yat says you move around the dummy because the dummy doesn't move or respond like a real "live" person, so you have to. He then discusses why other people's forms and dummy is different-irregular teachings by Yip Man, yet according to him, the correct sequence isn't important. Only that you have mastered and understood what you've learned.

The end of the book gives a layout and measurements on how to build a Wooden Dummy from 3 views as well as measurements for the arms and leg. The last 3 pages show 3 ink carvings of the history of Wing Chun done by Moy Yat.

-Dr. John Crescione

Thursday, 7 February 2013

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

The Historical Magazine Interview of Wing Chun Grandmaster Ip Man

Certain history only be interesting and exciting for certain people. Wing Chun Ip Man has a very good article to explore. I would like to collect articles, books, video tapes even DVD of all Wing Chun family Sifus around the world. Ip Man's original articles is one of the most precious collectable history. However, all this property should belongs to the museum, for the next generation. It's a never ending story.

Monday, 4 February 2013

Ip Man Ving Tsun Genealogy 葉問詠春世系圖譜

Ip Man Ving Tsun Genealogy

This is a book listing GGM Ip Man's Direct Students,

from Foshan to Hong Kong. It also lists his Grand

Students (his Students' Students), many with information

and photographs. All names are both in English and

Chinese.

Leung Kwok Ching, the Former Curator of the Museum

of Foshan contributed the foreword with a short

biography of GGM Ip Man "A Timeless Ving

Tsun Grandmaster.' GM Ip Chun also has an article

that chronicles his father's life from 1893 to 1972.

(articles are in both Chinese and English)

This book is printed by Ving Tsun Athletic Association in Hong Kong.

First edition; 2005

This is a book listing GGM Ip Man's Direct Students,

from Foshan to Hong Kong. It also lists his Grand

Students (his Students' Students), many with information

and photographs. All names are both in English and

Chinese.

Leung Kwok Ching, the Former Curator of the Museum

of Foshan contributed the foreword with a short

biography of GGM Ip Man "A Timeless Ving

Tsun Grandmaster.' GM Ip Chun also has an article

that chronicles his father's life from 1893 to 1972.

(articles are in both Chinese and English)

This book is printed by Ving Tsun Athletic Association in Hong Kong.

First edition; 2005

Saturday, 2 February 2013

Ving Tsun/Wing Chun Kung Fu for Young People

"Man must be himself, He cannot fight like a praying mantis; he doesn't know what a tiger feels and thinks: he must use his intellect as nature intended."

Kung Fu for Young People: The Ving Tsun System

by Russell Kozuki and Douglas Lee (Lee Moy Shan)

This was written in 1975 with 128 pages in black and white photos. Probably the rarest and least known of the early kung fu books. A small hardcover book by Sterling Publishers gives you so much conceptual bang for you philosophical buck. It also has the first cover of a woman doing Wing Chun self defense on the cover and throughout the book.

The book also shows many higher level classical techniques like Kwai Jarn (Biu Jee) and Kwun sao/Po Pai Jern. The book opens immediately with the centerline theory and what the term "kung fu" really means. It then goes into the various stances and introduces us to the triangle (front stance) stance-sam kwok mah, as well as the Hau Mah or back stance and single leg, or Golden Rooster stance. The triangle stance is used with a 50/50-weight distribution while the back stance has an uneven (70/30?) position.

The book covers various kung fu styles, names and philosophical concepts regarding each style and then compares them to Wing Chun. Paraphrased it says, "Man must be himself, He cannot fight like a praying mantis; he doesn't know what a tiger feels and thinks: he must use his intellect as nature intended."

The next chapter is on blocking hands-tan, bong fook, kwun sao and upper/lower gong sao. Followed next by a chapter on single hand, rolling hands and pak sao exercise. Almost all the techniques are done by Aimee Lee as the Wing Chun practitioner while Moy Yat disciple Cheng Moy Four does the attacking.

Attacking techniques follow, defining the center punch, Chung Kuen as "a bullet on a spring", straight and side palm strikes, lan sao usage-an obstruction and collapsing bong sao, bong sao/lop dar. Bil Sao is taught as a blocking hand, and to change the line of defense, intercepting and jamming theories with tan dar and chung kuen, the jip sao elbow breaking from Chum Kiu and the Lut Sao, Jik Chung theories as they apply to fighting.

The remainder of the book goes into various self-defense situations, Wing Chun style, against punches and grabs. Huen Sao and Jut sao are introduced here in the fighting sequences, as well as Bok Jarn (shoulder striking) Kwai Jarn and Po Pai Jern.

The final chapter covers kicking attacks and defenses using hands and feet together, intercepting techniques with kicks against kicks such as Fung gerk (think of Pak Sao with the bottom of the foot, right up the middle), bong gerk-knee in foot out, Kwai Shat-a knee break against a sweep, intercepting on a roundhouse kick and attacking the pole leg concept. The co-author Lee Moy Shan is showed doing the techniques with Cheng Moy Four. The book ends with a small history of kung fu and Yim Wing Chun.

This book is a rare gem when you consider the time period vs. general knowledge of the martial arts, as well as Wing Chun theory, history different level techniques, concepts and philosophy.

*A review by Dr. John Crescione

Kung Fu for Young People: The Ving Tsun System

by Russell Kozuki and Douglas Lee (Lee Moy Shan)

This was written in 1975 with 128 pages in black and white photos. Probably the rarest and least known of the early kung fu books. A small hardcover book by Sterling Publishers gives you so much conceptual bang for you philosophical buck. It also has the first cover of a woman doing Wing Chun self defense on the cover and throughout the book.

The book also shows many higher level classical techniques like Kwai Jarn (Biu Jee) and Kwun sao/Po Pai Jern. The book opens immediately with the centerline theory and what the term "kung fu" really means. It then goes into the various stances and introduces us to the triangle (front stance) stance-sam kwok mah, as well as the Hau Mah or back stance and single leg, or Golden Rooster stance. The triangle stance is used with a 50/50-weight distribution while the back stance has an uneven (70/30?) position.

The book covers various kung fu styles, names and philosophical concepts regarding each style and then compares them to Wing Chun. Paraphrased it says, "Man must be himself, He cannot fight like a praying mantis; he doesn't know what a tiger feels and thinks: he must use his intellect as nature intended."

The next chapter is on blocking hands-tan, bong fook, kwun sao and upper/lower gong sao. Followed next by a chapter on single hand, rolling hands and pak sao exercise. Almost all the techniques are done by Aimee Lee as the Wing Chun practitioner while Moy Yat disciple Cheng Moy Four does the attacking.

Attacking techniques follow, defining the center punch, Chung Kuen as "a bullet on a spring", straight and side palm strikes, lan sao usage-an obstruction and collapsing bong sao, bong sao/lop dar. Bil Sao is taught as a blocking hand, and to change the line of defense, intercepting and jamming theories with tan dar and chung kuen, the jip sao elbow breaking from Chum Kiu and the Lut Sao, Jik Chung theories as they apply to fighting.

The remainder of the book goes into various self-defense situations, Wing Chun style, against punches and grabs. Huen Sao and Jut sao are introduced here in the fighting sequences, as well as Bok Jarn (shoulder striking) Kwai Jarn and Po Pai Jern.

The final chapter covers kicking attacks and defenses using hands and feet together, intercepting techniques with kicks against kicks such as Fung gerk (think of Pak Sao with the bottom of the foot, right up the middle), bong gerk-knee in foot out, Kwai Shat-a knee break against a sweep, intercepting on a roundhouse kick and attacking the pole leg concept. The co-author Lee Moy Shan is showed doing the techniques with Cheng Moy Four. The book ends with a small history of kung fu and Yim Wing Chun.

This book is a rare gem when you consider the time period vs. general knowledge of the martial arts, as well as Wing Chun theory, history different level techniques, concepts and philosophy.

*A review by Dr. John Crescione

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)